“You wanna hear my robbery tactics?” says the rangy 48-year-old sitting opposite me in a Soho ramen house. “I’d make friends with the kid that was not that popular. I’d go to his house. I’d find a house key and secretly make a copy. Then I’d find out the schedule of the family. Then, when they were gone, I’d make my move. I was that kind of robber.”

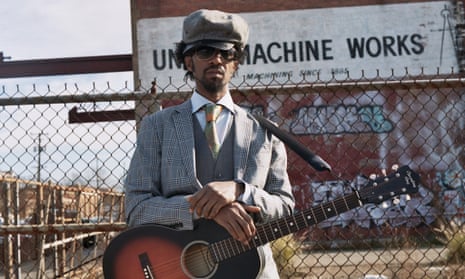

Ask Xavier Dphrepaulezz (it’s pronounced “dee-FREP-ah-lez”) about any of his past lives – including his teenage years of petty crime while in foster care – and he has a way of taking you to the heart of the action. His story is, by any criteria, extraordinary, and the enjoyment he derives from sharing it is infectious.

The singer, who describes himself as a lifelong hustler, landed in London this morning for the first time in a decade. Last time he was here, long before his current incarnation as Fantastic Negrito, he was briefly the blue-haired frontman of Blood Sugar X, a manic Cali-funk-punk collective “in the tradition of bands like Bad Brains and Fishbone”. Ten years earlier, he was simply Xavier, peddling innocuous MTV funk before a car crash put him in a coma for three weeks and laid his pop star aspirations to waste. Far from distancing himself from all these personas, Dphrepaulezz places his phone on the table and Googles them for you, lest you imagine he has anything to hide.

After half a lifetime spent chasing a break, Dphrepaulezz’s luck turned when he stopped trying. To start with, there was the DIY video for his song Lost in a Crowd, which last year saw off more than 7,000 allcomers to win the National Public Radio (NPR) Tiny Desk competition. He was railroaded into submitting the song by the other members of Blackball Universe, the Californian arts cooperative he co-founded to create a structure of mutual support among struggling black artists. Dphrepaulezz’s prize was the chance to follow in the footsteps of Adele and Florence and the Machine – and record a concert for NPR.

One person who connected with Dphrepaulezz’s urgent blues epistles was Bernie Sanders. It’s easy to see why a man running for the Democratic presidential nomination on a leftwing ticket might seize on, say, a song called Working Poor. When Sanders heard it, he enlisted Dphrepaulezz to play at events around the primaries in New Hampshire and Nevada. On the day we meet, the singer will be beamed across the US, thanks to a performance in Fox’s music industry drama Empire. That’s Fantastic Negrito you can also hear on Ron Perlman’s Amazon series Hand of God: the show’s theme song is the battle-weary testifying of An Honest Man.

Dphrepaulezz seems as much a bemused onlooker as a participant in the events of his life. The first time he heard any of the blues records that inform Fantastic Negrito’s debut album, The Last Days of Oakland, their concerns seemed a world away from his own. Aged eight, Dphrepaulezz was visiting relatives in south Virginia. The music playing in their house bore as little relevance to his life as the classical-pop records favoured by his father – a half-Somalian, half-Caribbean restaurateur born in 1905. Until the age of 12, home for Dphrepaulezz and his 14 siblings was rural Massachusetts. “My dad was a strict Muslim. He had a lot of rules,” he recalls. You probably have to be strict, I suggest, if you’re raising 15 kids. “Well,” he shoots back, “he wasn’t strict when he was making them.”

When the family moved to California in 1979, setting up home across the bay from San Francisco in Oakland, they were in effect releasing him into the wild. Gang-controlled drug-dealing had brought the city to the brink of lawlessness. Confronted by “this explosion of counterculture” – hip-hop, thrash metal and punk all meeting in one location – Dphrepaulezz made new friends, left home and didn’t come back.

“We were all selling drugs, man. We all carried pistols. There was a crack epidemic. Mostly, I was small-time. I was the kind of kid who would sell fake weed, shit like that. Sometimes I would use tea. What was it that the Beatles would smoke from a pipe in order to try and get high? Typhoid?” Typhoo tea? “That’s the shit!”

Dphrepaulezz’s saving grace was that, even as a teenage drug-dealer, he avoided ingesting anything heavier than weed. This period, spent pinballing between foster families, seems to have hardened his political outlook. “As long as we have have predatory capitalism,” he says, “we’ll have guns, because the gun industry loves to make money out of guns. They don’t care if children die. What concerns them is profit.”

Dphrepaulezz rarely gets emotional when going over these distant memories. But the death of Prince is another matter. “His Dirty Mind album changed everything for me,” he says, momentarily faltering. “Someone told me he was self-taught and that opened the door for me. I was 18 and getting into trouble. I was thinking, ‘What can I do that’s safe?’ So I started teaching myself how to play.”

His method was nothing if not ingenious. He “grew long sideburns” and pretended to be a student at the University of Berkeley. Taking the 40-minute bus ride north every day, he would head for its music rooms, copying students as they practised their scales. By day, he was not quite a student; by night, he was not quite a gangster. The realisation that he was “small-time” came when he and his friends bought some firearms from a gang, who returned to their house, held Dphrepaulezz at knifepoint and took the rest of their money. “The next day I got out. I hitchhiked to LA with $100 and a keyboard.”

There, Dphrepaulezz was surprised to find that a decade of hustling had been the perfect music business apprenticeship. A deal with Prince’s former manager was followed in 1993 by a $1m deal with Interscope, which he almost instantly regretted. Released in 1996, Xavier’s passable debut album The X-Factor pleased neither himself nor his hit-hungry paymasters. Three years of limbo ensued, which were broken one Thanksgiving evening. Dphrepaulezz’s car was hit by a drunk driver who ran a red light. “I fishtailed and rolled over four lanes of traffic.” The first thing he remembers after waking up three weeks later was the sensation of having a beard – not that he could lift his arms to feel it. The accident had broken both his arms and his legs, leaving his strumming hand mangled.

Far from sending him into freefall, Dphrepaulezz says the crash “released” him. Interscope terminated his contract and Dphrepaulezz reverted to the only other thing he knew: the hustle. Noticing that the only nightclubbing opportunities in LA involved “$20 for parking, $20 to get in, and at least $20 when you’re in, I converted the warehouse where I lived in South Central into an illegal nightclub. I knocked down a few walls and built a bar that looked kind of like a pimps-from-outer-space thing. Velvet movie theatre seats. A hot tub on the roof. Nude body painting.”

When Club Bingo wasn’t paying host to a clientele that included Alicia Silverstone, Mike Tyson and Eric Benét, its creator was working under a bewildering array of alter egos – among them Chocolate Butterfly, Me and This Japanese Guy and the aforementioned Blood Sugar X – and licensing material to film and TV shows.

When he and his Japanese partner had a son, he stopped looking for further incarnations, sold all of his equipment except for one guitar, moved back to Oakland and bought himself a smallholding with no greater plan than to supplement his publishing royalties by growing “medical marijuana” and eating homegrown corn, tomatoes and freshly laid eggs.

Five years had elapsed since he last played his guitar. His fingers were still crooked from the accident, but he had just enough mobility to play a G chord for his son in an attempt to stop him from crying. “His entire face changed,” recalls the proud father. He learned the Beatles’ Across the Universe and played it to him every night for a year.

With that came a slew of new songs, informed this time by the blues records that had bewildered him on that childhood vacation in Virginia. “In the middle of the conflict between me myself and lies / I saw people die for nothing / I sold coke to hungry eyes,” went his first song, Night Turned to Day. Together with Malcolm Spellman, his longtime Oakland friend who would go on to write Empire, Dphrepaulezz threw his publishing royalties into the Oakland art gallery, label and creative space that became their Blackball Universe cooperative. Within strolling distance is the Blues Walk of Fame, which commemorates musicians who passed through the city in its pre-gentrification days. “Black roots music is part of our story here,” says Dphrepaulezz. “Our art comes from their struggle. You think of that and you stay humble.”

But to really understand why Dphrepaulezz is now succeeding, you have to see him in action. A few days later, at London’s Rough Trade East, near the end of an electrifying performance, he plays Lost in the Crowd. As his clawed hand plays the last chord, he loosens his neck tie, leans into the mic and revisits its inception. “My collective calls me a narcissist,” he tells the crowd. “They were like, ‘Will you stop writing about yourself? Go look at people! Look around! Aren’t people interesting to you?’ So they sent me off to Berkeley, San Francisco, and told me to watch people for a day. Just sit and watch. So that’s what I did. And that’s what this song is.”

It’s surely no surprise that Dphrepaulezz sees his own values reflected in those of Sanders. It was the collective power of a wider group that launched Fantastic Negrito on to the world, while the “predatory capitalism” against which he rails almost claimed him before he reached adulthood. Back at the ramen house, he tries one more time to make sense of the past few years. “I thought my story was over. But that was when I realised I finally had a story to tell – and it seems to remind people of their own story.”